Little Machine, Big Results

At 22 weeks pregnant, La’Shondia Palmer couldn't breathe well enough for one — much less two.

In April 2016, she went to the hospital in Starkville, Mississippi for the second time in a week. Three days earlier, she felt like she was coming down with the flu, but after testing negative, she was released with an inhaler. This time, doctors rushed her to the ICU because her lungs were filling with fluid. The Starkville hospital couldn’t provide the support she needed, so she was airlifted to Baptist Memorial as her husband, daughter and church family raced to meet her in Memphis.

“I was scared,” Palmer said.

“I thought I was going to die.”

When a ventilator couldn’t dry out her lungs, the walls began closing in. “When my daughter came up to see me I told her, ‘Just save the baby’ – I thought I was going to die,” recalls Palmer.

Tests uncovered a lethal combination of swine flu and acute respiratory distress syndrome, or ARDS. “That’s when Dr. Jain said that she had a 10 percent chance of living,” said her husband, Mianju Delk. Dr. Manoj Jain, the infectious disease specialist in charge of Palmer’s care, considered one final option – supporting her through extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or ECMO.

What is ECMO?

When a ventilator fails to help a patient breathe, an ECMO machine can "breathe" for a patient by directly oxygenating their blood.

Normally, the lungs inhale oxygen and exhale carbon dioxide and the heart pumps oxygenated blood throughout the body. But by bringing out the blood in a tube, an ECMO system can add oxygen to the blood and remove the carbon dioxide, so a patient doesn’t need to breathe at all.

Baptist’s ECMO program is lead by Dr. John Craig, one of our top thoracic and cardiovascular surgeons. His team looks for patients who might qualify for this cutting-edge and potentially life-saving treatment. “Palmer had almost no functioning lung tissue. She shouldn't be alive,” Dr. Craig said.

“Dr. Craig was the last resort,” said Delk. The ECMO team raced his wife upstairs while Dr. Craig talked through the procedure and her chances. “I didn’t have a stable feeling that everything was going to be fine until after I spoke with Dr. Craig and God just reassured me that this miracle was going to take place,” Delk recalled. “He told my husband, ‘I’m going to go ahead and perform surgery on your wife like I was doing it on my wife.’ “That made him feel so good, he was in tears,” Palmer said.

“Palmer had almost no functioning lung tissue. She shouldn't be alive.”

Palmer was the first pregnant patient to be successfully supported by ECMO. “It’s amazing to see the degree to which someone can get sick and still recover,” Dr. Craig said. He compares ECMO to an umbilical cord – just like her baby received oxygen through an umbilical cord, Palmer’s blood was getting life-saving oxygen through ECMO.

Not only did she survive, her son did as well. Christopher Gabrian Delk was born healthy in August 2016. Palmer remembers holding Christopher in her arms for the first time. “Oh...It was a blessing. I was happy.”

A Happy Ending

Read an article from The Commercial Appeal about the day Dr. Craig took La’Shondia Palmer off of ECMO.

Read the Article

ECMO may sound magical, but it doesn’t heal a patient – it’s a support device, similar to dialysis.

When a kidney fails, dialysis machines provide support by performing the kidney’s function. When ECMO is used to oxygenate blood, it gives the heart and lungs a break, which helps the patient’s body recover.

“The body has an amazing ability to heal itself. Just as it can heal itself from a sore throat, the lung can repair itself,” Dr. Craig says. “As a cardiologist, it’s weird – instead of going in and fixing a heart problem, we put a patient on a support device and let the patient’s body fix itself.”

Though innovative, the concepts behind ECMO aren’t new. Doctors pioneered the idea in the 1950s, by connecting a patient and a healthy person together through their bloodstreams. The healthy person breathed for two, sharing the oxygenated blood. In the 1970s, Dr. Robert Bartlett prototyped the first mechanical ECMO system using a version of the heart-lung machine used in surgery.

How ECMO Works

1Blood is drained from the body from a primary artery, infused with fluids and heparin, and run through a pump mechanism.

2The blood is then moved through an oxygenation chamber and mixed with a formula of O2 and CO2 served through a chemical blender.

3The oxygenated blood is then warmed before being served back into the body, usually through an artery in the neck.

Baptist Memorial Hospital-Memphis purchased its first ECMO machine in 2013 with the help of a generous donation from the Baptist Foundation, joining 148 centers in the country that provide treatment through this frontier life-support system.

In the past three years, Baptist has used ECMO to support 60 patients, half of those past year. “As we see our volume increasing, our need is increasing,” Dr. Craig says. To meet increasing demand, the team is pursuing a fourth ECMO machine.

Not every patient is a good candidate for ECMO. It’s difficult to use, timing is crucial and it requires a lot of resources. Though ECMO is not an indefinite life-support device, it can provide a short-term solution when a patient’s heart or lungs fail. To be a considered for ECMO, a patient must have a reversible condition. Like La’Shondia Palmer, candidates typically develop life-threatening complications after contracting the flu.

The Walking Dead

ECMO patients don’t need to breathe because the machine is doing it for them. Their lungs are, in Dr. Craig’s words “Not compatible with life.”

Looking at the X-rays of ECMO patients, Dr. Craig says, “There is no way these people should be alive – the lungs are (normally) black. Here, there’s no functioning lung tissue, it’s all white. Providers are seeing X-rays they’ve never seen as bad as those because patients will die before their X-rays look this bad.

In January 2012, 20 year-old Matt Parker complained of a flu-like illness.

The usually healthy college student had become so weak that his concerned parents traveled two hours from their home in Cabot, Ark. to drive him from his dorm room to the nearest hospital.

Parker was so short of breath that he had to communicate with his parents via text, and so weak that his father carried him downstairs. At a Jonesboro hospital, he was sedated and hooked to a ventilator. Troubled doctors informed his family and friends that the he wasn’t going to make it.

However, one of Parker's doctors had heard of ECMO and identified him as a potential candidate. After a quick phone call to Baptist, Parker was put on the next MedFlight transport to Memphis.

A Slim Chance

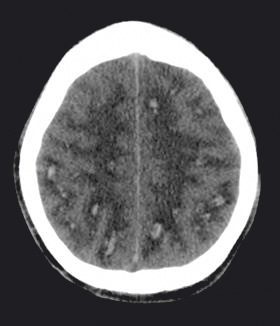

This is an X-ray of Matt Parker’s brain. “This is just one slice, and there’s probably 50 different slices all with this level of bleeding,” Dr. Craig explains.

The Memphis team was unsure if Parker would survive. If he did, as a straight-A college student, he had a lot to lose, neurologically speaking. “We put him on ECMO, but the infection ate large holes in his lungs. Eventually, it got to his brain and caused 100 little bleeds,” Dr. Craig said.

After about a month on ECMO, Parker had survived the worst of his illness. After fully recovering at a rehab center in Atlanta, he was able to return to his studies and graduate college. If not for the quick-thinking doctor in Jonesboro, the outcome could have been very different.

“There are a lot of dying young people simply because they didn’t know this support existed,” Dr. Craig explains. “If anyone thinks about it and knows how to reach us – even if they think it’s a situation that’s hopeless – they can give us a call.”

Through ECMO, Matt Parker survived a nearly deadly case of the flu. Parker was able to thank Dr. Craig personally at his wedding.

Two years after his hospital stay, Parker’s relationship with Dr. Craig endures. When he got married, he invited Dr. Craig, who drove two hours to celebrate the nuptials. “I saw the whole community of friends, family members, the wife’s family, it was overwhelming to see,” Dr. Craig said. “That day was made possible by this technology. It was a very special day.”

Parker was happy to thank Dr. Craig in person. “He thought it was remarkable to see how well I was doing and showed me my brain scans. He loves what he does – you can tell that he’s not just concerned for you as a patient, but he really cares for you as a person.”

Dr. Craig says, “The science is really interesting, but the fact that we can relieve suffering and prolong life is the big story.”